Birthday Problem: Have you ever walked into a room and wondered: “What are the chances that two people share a birthday?” You might think it’s low unless the room is huge — but the Birthday Problem proves otherwise. This fascinating probability paradox surprises even math enthusiasts.

What is the Birthday Problem?

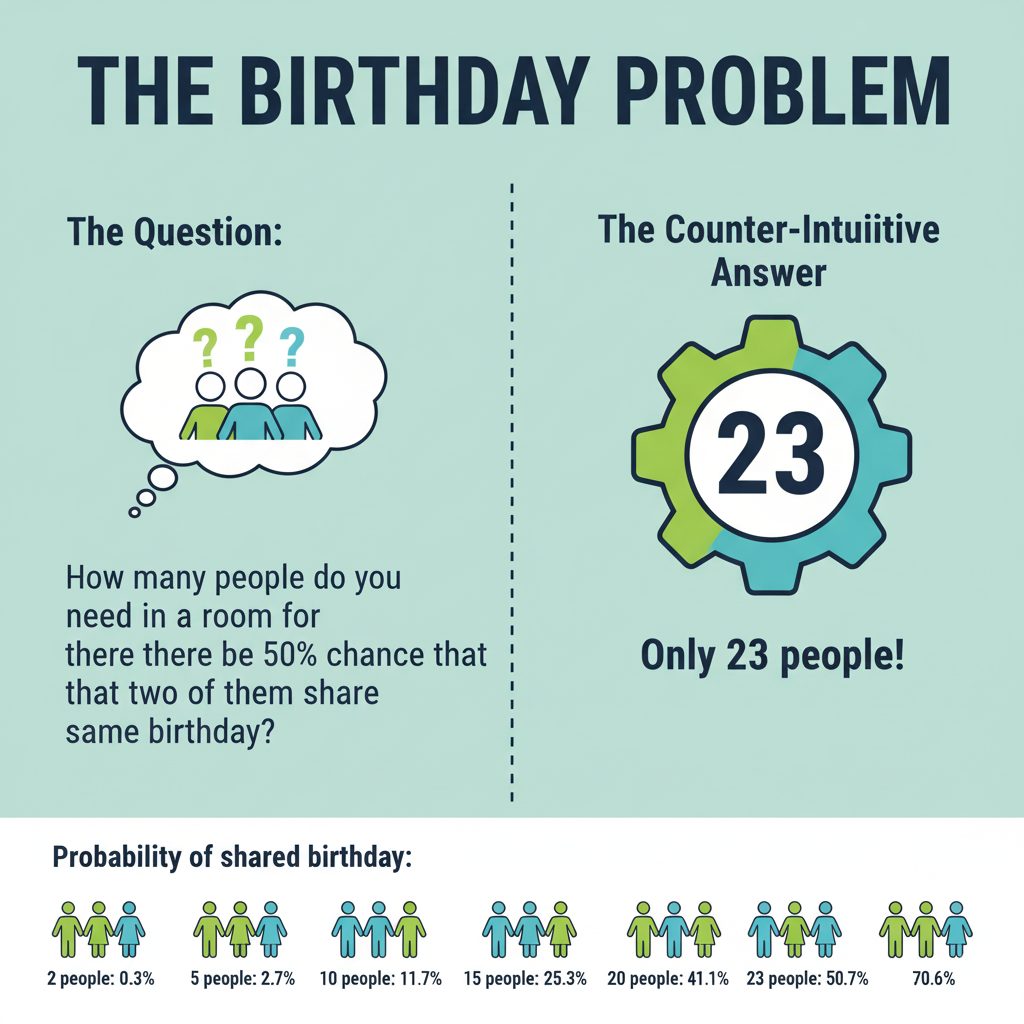

The Birthday Problem (also called the Birthday Paradox) asks:

In a group of n people, what is the probability that at least two of them share the same birthday?

Even though there are 365 days in a year, the probability of a shared birthday rises rapidly with group size — much faster than intuition suggests.

How It Works

It’s easier to first calculate the chance that no one shares a birthday, and then subtract that from 1.

- Assume 365 days in a year (ignore leap years).

- For the first person, any birthday is fine: 365/365=1365/365 = 1365/365=1

- For the second person, their birthday must avoid the first person: 364/365364/365364/365

- For the third person, avoid the first two: 363/365363/365363/365

…and so on.

Probability that no one shares a birthday:

P(no shared birthdays) = 365/365 × 364/365 × 363/365 × ... × (365 - n + 1)/365

Probability that at least two share a birthday:

P(at least 2 share) = 1 - P(no shared birthdays)Surprising Examples

| Number of People | Probability of Shared Birthday |

|---|---|

| 10 | 11.7% |

| 20 | 41.1% |

| 23 | 50.7% |

| 30 | 70.6% |

| 50 | 97.0% |

Key insight: With just 23 people, there’s about a 50% chance that two share a birthday. That’s why it’s called a paradox — it seems counterintuitive!

Why It Matters

- Probability & Statistics: A classic example in combinatorics and probability.

- Cryptography: Inspired the “birthday attack” in hashing algorithms.

- Fun Fact for Parties: Even a small gathering can have a shared birthday — now you know why!

Also Read : Birthday Effect: Why More People Die on Their Birthday

Quick Facts

- Assumes 365 days per year.

- With 50 people, probability exceeds 97% — almost certain.

- Demonstrates how human intuition can underestimate probability.

Conclusion

The Birthday Problem shows that our intuition about probability can be very wrong. Just 23 people in a room gives a 50/50 chance of a shared birthday, while 50 people almost guarantees it. Understanding this paradox is not just fun — it has practical applications in math, statistics, and cryptography.